Short stories & novels

“Short stories are tiny windows into other worlds and other minds and other dreams. They are journeys you can make to the far side of the universe and still be back in time for dinner.” - Neil Gaiman

Introduction

The short story is one of the literary genres that you will encounter most often during the lessons, and with good reason. One of the key strenghts of the genre lies in its brevity 1. There is no exact definition as to when a short story exceeds 2 its genre, thus becoming a novella or a novel, or on the other hand too short, becoming merely an anecdote, but most of the short stories that we read during the lessons are less than ten pages. Like the short story genre, novels are equally undefined 3 in length, although some publishers allegedly defines novel-length as 50,000-110,000 words.

Given the limited amount of space, the short story needs to be very

concise

4 in its communication and therefore it is often characterised by:

- Revolving around only one conflict, experience or situation

- Including a small number of characters

- A rather short time span

- A certain dramatic structure

In order to conduct 5 a thorough analysis of a short story or a novel, it is not enough to look at the characteristics mentioned above. There are several different approaches 6 to analysing works of fiction, but the typical approach would be new criticism, and the terms presented below.

The Setting

Introduction

The setting provides the backdrop 1 of the story and therefore it very important that the author establishes 2 an interesting and believable setting in order to draw the reader in. In an analysis of the setting, a number of things can be examined.

Time

Time can be a

diverse

3 matter. The fairytale genre

utilises

4 an unspecific time frame through phrases such as once upon a time to establish a magical setting, whereas other genres seek to

employ

5 realism by specifying the year and day, perhaps even hour or second.

Furthermore, the use of

symbolism

related to the concept of time might be of great importance to the meaning of a text. Night and day or seasons, such as spring or winter, indicate time, but can also be perceived as symbols of youth, death, beauty, growth and so on.

A Song of Ice and Fire

(1996-), provides an example of this through the

catchphrase

6, winter is coming. The phrase does not only suggest that winter is approaching, but so are the series' all-destroying

antagonists

, The White Walkers.

Place

The notion 7 of place in a text might be just as definable or indefinable as the notion of time. An example of a fairly specific, physical setting can be found in F. Scott Fitzgerald 's The Great Gatsby (1925) which takes place on Long Island, New York. In contrast, some authors make use of more metaphorical 8 settings. An example of this is Virginia Woolf 's short story The Mark On The Wall (1917), whose most interesting setting appears as thoughts in the narrator's mind. It often makes more sense to speak of the mood or atmosphere of a text, rather than a metaphorical or mental setting.

Environment

The environment 9 of a setting, usually helps to explain the characters. By understanding the environment in which the text takes place, it might be easier to understand why a certain character acts or feels the way that he or she does. Often, the environment of a setting portrays a certain social class, for instance Charles Dickens 's Oliver Twist (1845) that portrays the hardships of the working classes, as opposed to the more prosperous 10 upper classes in Victorian London.

Mood & atmosphere

A-level students are often required to focus on abstract 11 concepts, such as the mood 12 or the atmosphere 13 of a text. Although, these elements can also be examined through e.g. the attitudes or thoughts of the characters, they are often closely tied to the creation of the setting. Mood and atmosphere serve the purpose of trying to emotionally affect and encourage 14 the reader to channel a certain mood while reading the text. Adjectives and adverbs , in particular, play a great role in affecting the reader and establishing these emotions. In Harper Lee 's To Kill a Mockingbird (1960) a certain mood and atmosphere of boredom and nothingness is created in relation to the fictional Maycomb County, Alabama.

A day was twenty-four hours long but seemed longer. There was no hurry, for there was nowhere to go, nothing to buy and no money to buy it with, nothing to see outside the boundaries of Maycomb County.

Characters

Introduction

One of the first things that pops into our heads when thinking of a work of fiction, is the characters. Well-constructed characters are capable 1 of creating an emotional 2 bond between the reader and the character. It sparks 3 identifcation, but also serves the purpose of driving the plot forward. There are obvious reasons as to why a character such as Hermione Granger is more likeable than Draco Malfoy , but both characters are explicitly 4 and carefully characterised. Characterisation 5 is one of the strongest assets 6 that a writer possesses in terms of engaging the reader in the text, and therefore also one of the most interesting in terms of analysis.

External & internal characterisation

External 7 characterisation refers to the aspects of a character that are visible from the outside. Examples of this could be appearance, age, gender etc. internal 8 characterisation, on the other hand, examines the things that cannot be seen on the surface 9 of a character. Therefore, things such as intelligence, emotions, mood and mental aspects are of great importance when carrying out an internal characterisation.

Direct & indirect characterisation

Besides speaking about the inner and outer aspects of a character, it is also interesting to examine how the portrayal 10 of the character is executed 11. Generally speaking, two terms exist, direct characterisation and indirect characterisation.

Julia was twenty−six years old. She lived in a hostel with thirty other girls [...] She was 'not clever', but was fond of using her hands and felt at home with machinery. She could describe the whole process of composing a novel, from the general directive issued by the Planning Committee down to the final touching−up by the Rewrite Squad. But she was not interested in the finished product. She 'didn't much care for reading,' she said.

As seen in the excerpt 12 above, the reader is introduced to Julia. The reader does not have to guess her age or intelligence based on dialogues and actions, but is instead directly informed by the narrator.

"Oh! Single, my dear, to be sure! A single man of large fortune; four or five thousand a year. What a fine thing for our girls!"

"How so? How can it affect them?"

"My dear Mr. Bennet," replied his wife, "how can you be so tiresome! You must know that I am thinking of his marrying one of them."

One could argue that a lot of information is directly presented in the excerpt above, but it is still presented through the words of the characters and not directly by the narrator. Well-constructed characters are usually portrayed and developed 13 through a combination of direct and indirect characterisation. Direct characterisation may have the advantage of precision, but indirect characterisation encourages 14 the reader to draw upon his or her imagination 15 and interpretation 16.

Flat, round, static or dynamic

In analysing the characters of a text, the concepts of flat and round characters might also be useful. The term flat character refers to a two-dimensional 17 character that does not contain 18 a lot of depth 19, whereas the term round character refers to a more complex, three-dimensional 20 character with more information attached 21. As a rule of thumb, most protagonists and important characters are round whereas more insignificant 22 characters are usually flat. Closely related to these terms, is the notion 23 of static and dynamic characters. A static character is a character that does not change or evolve 24 throughout the course of the text, but instead stays pretty much the same all the way through, as is the case with most antagonists . A dynamic character, on the other hand, refers to a character, typically the protagonist, that undergoes a transformation or process of some sort.

Other useful terms in the analysis of characters are stock characters , pivotal characters , personal characteristics and social characteristics .

Narrator

Introduction

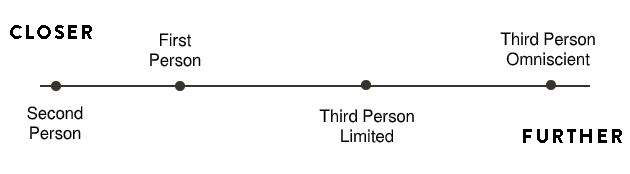

Who tells the story? The question sometimes produce 1 a quick and easy answer, whereas other times it is not that simple. The three most common types of narrators are the first-, second- and third-person narrator.

First-person narrator

The first-person narrator can be identified by the use of personal pronouns such as I, we and me, suggesting that the text is narrated from a character's, often rather subjective, point of view and perspective. This is a quick way of establishing 2 sympathy and understanding for a protagonist. If the reader has direct access 3 to the thoughts behind a character's every move, it is hard to be completely unsympathetic to the character. There are, however, cases in which even a total access to the character's mind does not produce a sympathetic character. This is for instance the case in Bret Easton Ellis novel American Psycho (1991), where one rarely feels sympathy for the murderous and shallow 4 protagonist, Patrick Bateman.

Second-person narrator

The second-person narrator is identified by the use of the pronoun you, your and yours. The use of second-person narrators is quite rare in short stories and novels, but appears often in songs and poetry. A lot of Bob Dylan's songs utilises 5 the second-person narrator.With your pencil in your hand

You see somebody naked

And you, you say, "Who is that man?"

You try so hard

But you don't understand

Just what you will say

When you get home

Because something is happening here

But you don't know what it is

Do you, Mister Jones?

Third-person narrator

The third-person narrator makes use of pronouns in third-person such as he, she and even it in rare cases. Depending on the point of view, the use of a third-person narrator can, like the use of a first-person narrator, be quite effective in creating sympathy and establishing an emotional 6 bond between reader and character. Still, there might be an element of distance in the fact that the narrator is often not present in the text, as indicated by the use of third-person pronouns, but instead observing the text from the outside.

He no longer dreamed of storms, nor of women, nor of great occurrences, nor of great fish, nor fights, nor contests of strength, nor of his wife. He only dreamed of places now and the lions on the beach. They played like young cats in the dusk and he loved them as he loved the boy. He never dreamed about the boy. He simply woke, looked out the open door at the moon and unrolled his trousers and put them on.

Limited or omniscient

The first-person narrator usually one has access to his or her own thoughts, but very often a third-person narrator will have access to other character's thoughts as well. If the third-person narrator can jump back and forth between all of the character in a text, the narrator is refered to as a third-person omniscient 7 narrator. If this access is limited to only one or two characters, the narrator will be refered to as a third-person limited 8 narrator.

DISTANCE AND NARRATORS

Plot & Structure

Introduction

Analysing the plot and structure of a text can be a difficult task. A lot of authors have succesfully altered 1 and experimented with the traditional conventions 2 of storytelling in order to excite and surprise the readers. milestones 3 in experimental storytelling include James Joyce 's Ulysses (1922) and other modernist heavyweights 4 such as Ezra Pound , T.S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf . From an analytical point of view, the narratives 5 of fiction can, rather boldly 6, be divided into two; those that are linear and those that are not.

Linear narrative

A linear narrative places its events 7 in what is also commonly known as a chronological order. The events and sequences of the text move forward, in a linear manner 8, from A to B. This narrative form is quite common in shorter pieces of fiction, whereas it is more unusual for novels to maintain 9 a strictly linear narrative through the entire course of the story.

Complex narrative

It can seem a bit drastic to characterise an otherwise mostly linear narrative, perhaps with the exception of a few flashbacks , as a complex 10 narrative, yet as soon as a text employ 11 flashbacks, it can no longer be defined as linear.The complex narrative therefore has to contain 12 both the seemingly linear narrative with few flashbacks or flash-forward , but also the completely experimental, non-linear or even a backwards narrative structure.

Circular narrative

The circular 13 narrative refers to a narrative structure in which the plot returns to the beginning or a sense of status quo 14 is achieved at the end. This notion 15 exists in a lot of different variations ranging 16 from children's fairytales to horror fiction.

Another example from popular culture, is crime fiction that often sees the murderer, nemesis 18 or prime suspect escape at the end, thus leaving room for yet another instalment 19 and repetition 20 of the story.

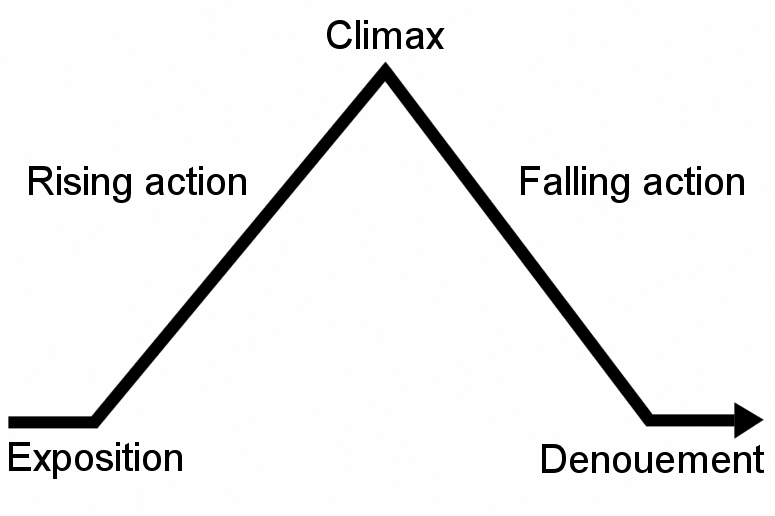

Freytag's Pyramid

Freytag's Pyramid exists in a lot of different variations depending on the genre to which it is applied. The German playwright Gustav Freytag first designed the model for the tragedy genre, which explains why it did not originally end in resolution, but rather catastrophe 21 as exemplified by the suicide of Romeo and Juliet (1594-1596) or the revelation 22 of Oedipus Rex (429 BC).

Other useful terms in the analysis of the plot and structure are foreshadowing , in medias res , suspense , frame story , stream of consciousness , set-up and pay-off , bildungsroman , epistolary novel, and present tense vs. past tense.

Themes

Introduction

The theme is defined as the greater motive, underlying meaning or idea of a text. It usually deals with universal emotions or conflicts and the theme itself is rarely mentioned directly in the text. Instead, the reader will have to read between the lines in order to uncover 1 the idea.

Growing up

Many works of fiction follow the transition 2 of the protagonist 3 from childhood through adolescence 4 and sometimes into early adulthood. J.D. Salinger 's Catcher in the Rye (1951), Stephen Chbosky 's The Perks of Being a Wallflower (1999), J.K. Rowling 's Harry Potter (1997-2007) and André Aciman 's Call Me by Your Name (2007) all examine this particular transition. Works of fiction that deal with the notion 5 of growing up, often also explore other related themes such as friendship, sexuality, identity, alienation 6, loss of innocence and love. The theme of growing up is also commonly refered to as coming-of-age.

Love

Love is a subject that never ceases 7 to inspire writers and it has been the subject of novels for centuries 8. Love is the catalyst 9 of classics such as William Shakespeare 's Romeo and Juliet (1594-1596), Emily Brönte 's Wuthering Heights (1847) and Jane Austen 's Pride and Prejudice (1813) but it is also the stuff of acclaimed 10 modern novels such as Sally Rooney 's Normal People (2018).

Good vs. Evil

The notion of good and evil is exemplified in almost every religion, philosophy, ideology and culture across the world. Especially works of fiction within the fantasy, fairytale and science fiction genres, have based countless narratives 11 upon this idea. Literary milestones 12 such as J.R.R. Tolkien 's The Lord of the Rings (1954-1955) and C.S. Lewis ' The Chronicles of Narnia (1950-1956) portray this battle explicitly, whereas other works, such as Joseph Conrad 's Heart of Darkness (1902), deal with the theme as an inner battle or conflict between good and evil.

Power

Power and its corrupt 13 nature is another theme that great authors have dwelled 14 upon for centuries. George Orwell 's Animal Farm (1945) and William Shakespeare's Macbeth (1606) are both prominent examples of this.

Man vs. nature, hate, death, courage, war, cultural differences and prejudices are some other examples of universal themes that exist across a great variety of genres, please note, however, that this list is inadequate 15.

Writing Style

Introduction

Words are anyone's to use, but yet the style of a writer is strangely unique. In fact, the renowned American writer, journalist and adventurer, Ernest Hemingway 's minimalistic, short prose 1 was so characteristic and unmistakable that he even did commercials just in writing. The term writing style refers to a number of different aspects of writing such as diction, tone, rhythm, vocabulary, syntax and figurative language.

Dialogues and descriptions

The use of dialogue 2 is a powerful assets 3, but also an important plot- device 4 in developing 5 realistic and engaging 6 characters, whilst allowing the writer certain stylistic liberties 7. The Irish poet and playwright, Oscar Wilde , often made use of dialogue for his characters to exhibit 8 the ironic and satirical 9 style of humour that became his trademark 10.

‘My dear old Basil, you are much more than an acquaintance.’

‘And much less than a friend. A sort of brother, I suppose?’

‘Oh, brothers! I don’t care for brothers. My elder brother won’t die, and my younger brothers seem never to do anything else.’

It is hard to set the stage without the use of descriptions 11, but on the other hand, characters and interrelationship 12 often lack definition 13 without the use of dialogues. In theory, there should be a balance between the amount of space that dialogues and descriptions take up respectively 14.

Yet, Hemingway has crafted enticing 15 works of fiction that are almost entirely dialogue-driven and the dystopian masterpiece Nineteeen Eighty-Four (1949) by George Orwell contains page after page filled with descriptions. In conclusion, rules are made to be broken.

There is something demoralizing about watching two people get more and more crazy about each other, especially when you are the only extra person in the room. It's like watching Paris from an express caboose heading in the opposite direction - every second the city gets smaller and smaller, only you feel it's really you getting smaller and smaller and lonelier and lonelier, rushing away from all those lights and that excitement at about a million miles an hour.

Descriptions are effective in setting the scene, however it does not always consist of picturesque 16 descriptions of the physical surroundings 17. American poet and writer, Sylvia Plath makes great use of passages describing the thought process of the protagonist, Esther, in her novel The Bell Jar (1963). This access 18 to the protagonist's mind helps to develop the character, while the word choices and especially Adjectives such as demoralizing, only, small and lonely, establishes an atmosphere of loneliness and alienation 19.

Local colour

A lot of fiction have been preoccupied 20 with the local character 21 and conflicts of a certain area, causing characteristics such as customs 22, traditions and dialects to creep 23 into the work and exemplify a unique style. An example of this is A Confederacy of Dunces (1980) by John Kennedy Toole . Sometimes these characeristics are not defined by a geographical area, but rather by a certain group of people leading to terms such as sociolects, slang and argot.

Other useful terms in the analysis of writing style include formal and informal language , stream of consciousness , point of view , expletives and non-standard English .

Title

Introduction

An analysis of the title is often something that you will need to consider whether contributes 1 to your analysis or is merely 2 stating the obvious. A lot of texts are for instance named after their main character, the titular 3 character, and while it provides an indication of who is important in the text, there is seldom 4 much to say on such titles. On the contrary, the title might be the very thing that binds everything together and provides the key to the interpretation 5.

Titular characters

William Shakespeare is only one in a series of renowned 6 writers that would name or refer to characters in the titles of his works. Shakespeare named or refered to the protagonist in the title of all his tragedies and historical plays, whereas his comedies mostly featured more explicit 7 titles. Other well-known examples include J.K. Rowling 's Harry Potter (1997-2007), Charlotte Brönte 's Jane Eyre , Bram Stoker 's Dracula (1897) and Charles Dickens ' Oliver Twist (1845).

Symbolic titles

Often, titles which do not reference a titular or protagonistic character of sorts, tend to feature more abstract and symbolical titles. These titles often suggest or hint at ways of interpreting the text. Harper Lee originally intended to name To Kill a Mockingbird (1960) after the most prominent character, Atticus Finch, but later opted 8 for the famous title. The title is referenced only once in the book, and in a literal sense, but it seems that there is a deeper meaning between the lines.

"Shoot all the bluejays you want, if you can hit 'em, but remember it's a sin to kill a mockingbird."

That was the only time I ever heard Atticus say it was a sin to do something, and I asked Miss Maudie about it.

"Your father's right [...] Mockingbirds don't do one thing but make music for us to enjoy. They don't eat up people's gardens, don't nest in corncribs, they don't do one thing but sing their hearts out for us. That's why it's a sin to kill a mockingbird."

Symbolism

Introduction

Symbolism is perhaps the single most powerful tool in adding depth 1, significance 2 and weight 3 to an object, situation, concept or character. It permits 4 the writer to emphasise 5 and add subtle 6 meaning to specific words or symbols within the text. A meaning that might only be discovered or understood by the chosen few. A lot of symbols and their representation 7 are, however, archetypal 8 and often even rehashed 9 ideas, which makes it easier for the avid 10 reader to spot the symbols.

Symbols

This is easier said than done, as symbols can be hard to spot and decipher 11. Furthermore, they do not always work outside the context of the text. There are, however, also a great deal of symbols, often derived from matters such as history, war and religion, where most readers have become almost accustomed 12 to the symbolic value. Examples of these symbols are hearts, red roses, white doves, apples and so on. It is important to note that the interpretation of symbols is, at least to some degree, based on the cultural background of the receiver. An elephant is a symbol of power, luck and wisdom, but in some Asian cultures it also represents an inconvenience 13 and a financial burden 14.

Metaphors & Similes

Metaphors and symbols are both central literary concepts, and it can be hard to distinguish 15 between the two. Metaphors act as comparisons between unrelated 16 ideas, as exemplified by playwright and poet, William Shakespeare 's quote, all the world's a stage and all the men and women merely players. The world is obviously not a stage, yet the metaphor is engaging 17. A closely, related term is the simile. A simile conveys 18 a direct comparison by using the words like and as. In his controversial novel Lolita (1955), Vladimir Nabokov poses 19 a string of similes:

In her washed-out gray eyes, strangely spectacled, our poor romance was for a moment reflected, pondered upon and dismissed like a dull party, like a rainy picnic to which the dullest bores had come, like a humdrum exercise, like a bit of dry mud caking on her childhood.

Drawing Parallels

Introduction

In written assignments it is quite uncommon 1 to draw parallels, unless it is in the form of a discussion at the end. It is, however, quite typical to end an oral 2 presentation or exam by drawing parallels and placing the text or subject in a wider context 3.

Other works

During the oral exam, it is mandatory 4 to draw parallels to other texts that have been discussed and analysed in class. The text analysed at the exam is unknown 5 to the reader, but it is thematically related to a course that has been examined in class. Examples of courses are e.g. Australia, Serial Killers or Hip Hop. These courses all have different focal points and most introduce new terms and technical language. Drawing parallels to such courses therefore consist of accounting 6 for the texts, terms and focal points 7 of the course.

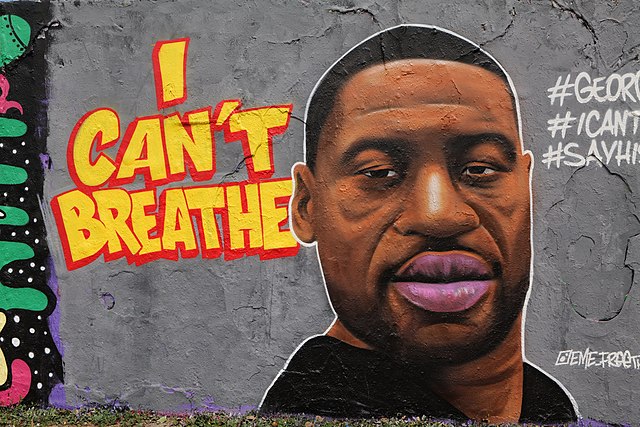

The real world

There is a good chance, that the work of fiction analysed is inspired by or share themes and events with those of the real world. An example is found in Kathryn Stockett 's The Help , which even though the story is fictional, is placed within a real world context. This provides the reader an opportunity to draw parallels to American history and even modern events such as the Black Lives Matter movement.

Literary criticism

Another way of placing the text in a wider context or putting another spin 8 on it, is changing or combining this analysis method, new criticism, with other forms of literary criticism such as historical criticism. This can provide for different interpretations of the text but can also be very useful in drawing parallels. There are several incidents of historical or personal contexts sneaking into literature, but prominent 9 examples are J.R.R. Tolkien 's The Lord of the Rings (1954-1955) and C.S. Lewis ' The Chronicles of Narnia (1950-1956) that were both, partially 10, written in England during World War II, and therefore it is likely to believe that the historical context of the war influenced 11 the stories.